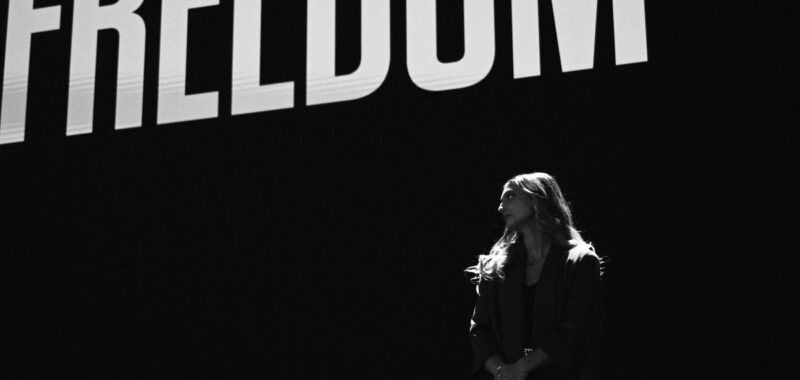

The most emotional moment of last night’s Democratic National Convention was supposed to be Joe Biden’s farewell, after his party’s power brokers made clear he could not run again. And true, his address showed a graciousness in defeat that Donald Trump could never hope to understand. But the most moving speech of the evening was only a few minutes long, and it was given by a young woman from Kentucky.

Her name was Hadley Duvall, and she spoke in a section devoted to the effects of abortion bans on regular people. She introduced herself as an “all-American girl,” a cheerleading captain, a homecoming queen—and a “survivor.” A decade ago, Duvall became pregnant at 12 after being raped by her stepfather, and she wanted to draw attention to Donald Trump’s description of abortion bans as a “beautiful thing.”

Duvall asked: “What is so beautiful about a child having to carry her parent’s child?”

The awfulness of what had happened to this young woman, and the dignity with which she recounted it, silenced the audience. Some delegates had tears in their eyes. Here in prime time, the Democrats were confronting their opponents with their support for laws that force 12-year-old girls to bear their rapists’ babies. Never mind weird; that’s obscene.

People want to know how this convention is different from the one that would have happened with Biden as the presidential nominee—and this feels like an obvious example. Kamala Harris is much more comfortable campaigning on abortion than Biden, who is an observant Catholic. Her team has grabbed back the word freedom to question why the government wants to dictate health-care decisions and interfere with women’s lives. “I can’t imagine not having a choice,” Duvall said.

Duvall, who is now in her 20s, miscarried naturally. Today, under Kentucky’s post-Roe laws, which are being challenged in court, she would not have been entitled to an abortion. (The state has no exception for rape or incest.) She was the star of a viral ad during Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear’s successful reelection campaign last year, and he followed her onto the convention stage, calling her “one of the bravest people I’ve ever met.” He then devoted much of his speech to reproductive rights.

Duvall appeared alongside three other speakers with similarly heart-wrenching stories. Amanda and Josh Zurawski were first shown in a recorded video, looking at the baby clothes they had bought for their daughter, Willow. But Amanda started to miscarry at 18 weeks, and Josh watched as doctors in Texas refused to use abortion drugs to induce labor until Amanda’s temperature spiked enough to turn the situation into a medical emergency—and thus make the use of abortifacients permissible under the state’s new, post-Roe laws. Next up was Kaitlyn Joshua, who had been turned away by two emergency rooms in Louisiana when she began to miscarry her second baby at 11 weeks. She also blamed the post-Roe landscape for her difficulty in getting medical attention.

The segment reflected the Democratic belief that Republican leaders have lost touch with the median American opinion on abortion. Almost two-thirds of Americans say abortion should be legal in most cases, but almost zero percent of people at the Heritage Foundation seem to believe the same. The much-publicized Project 2025—a governmental blueprint drawn up by the powerful think tank that got regular name-checks yesterday—asserts that abortion is “not health care.” (The document mentions abortion 143 times in its 54-page chapter on health care, which seems like a contradiction.) Project 2025 calls for more stringent regulation of the manufacturers of abortion pills; research on the “harms” of abortion to women and girls; restrictions on the mailing of pills; a ban on the use of government money to fund abortion travel; and defunding Planned Parenthood.

Overall, the message is: Overturning Roe v. Wade was just the beginning. The trouble is that, for many voters, overturning Roe was already too much.

Project 2025 was published last year, but it has entered public consciousness in the past few months as Democrats have begun to use it as placeholder text for “bad stuff the Republicans want to do.” Here at the convention, it crept into speeches across the first night, and Michigan State Senator Mallory McMorrow even brought along her own bound copy, asserting that Republicans “went ahead and wrote down all of the extreme things that Donald Trump wants to do in the next four years.”

As my colleague David Graham wrote recently, Trump has tried to distance himself from Project 2025, presumably because it polls about as well as halitosis. “I disagree with some of the things they’re saying and some of the things they’re saying are absolutely ridiculous and abysmal,” Trump posted on Truth Social. The Heritage Foundation’s document even gestures to how unpopular full abortion bans are in practice, noting: “Miscarriage management or standard ectopic pregnancy treatments should never be conflated with abortion.” Yet this is exactly what happens: The drugs are the same, and doctors in Louisiana and elsewhere have said that the threat of prosecution for providing such medical care has a chilling effect.

Trump has toned down the party’s platform on abortion—but in today’s media environment, voters are highly attuned to the idea of secret plans and what they’re not telling you. The same conspiracism that Trump has tried to inculcate in his voters might now backfire on him. After all, his Supreme Court appointments allowed Roe v. Wade to be overturned, and red states have enthusiastically pursued federal abortion restrictions since. The existence of Project 2025 gives voters permission to believe that a second Trump presidency would create far more restrictions on abortion, whatever he claims now.

When the Dobbs decision leaked in 2022, I wrote about Ireland’s referendum on abortion four years earlier. Then, a deeply religious country had voted by a decent margin to permit terminations up to 12 weeks, with no restrictions. Why? Because the country’s ban on abortion was held responsible for the 2012 death of Savita Halappanavar, a 31-year-old dentist who started to miscarry at 17 weeks. Afraid of being prosecuted, Irish doctors administered the necessary drugs only when they no longer detected a fetal heartbeat. It was too late to save Halappanavar. She died of blood poisoning—the same fate Amanda Zurawski so narrowly avoided. An inquiry into the case found that if Halappanavar had been given abortion drugs when she first presented at the hospital, “we would never have heard of her, and she would be alive today.”

The success of Ireland’s abortion-rights campaign showed that activists had found a way to talk about the issue that appealed to conservatives and older people, the two groups most likely to have qualms about the practice. Some feminists grumbled about foregrounding “good abortions” and medical cases, rather than defending the principle more widely, but the campaigners’ strategy worked. (Contrast this with Planned Parenthood’s stunt of offering pill-based abortions near the convention center this week, which was seized upon by the right as evidence that the left treats the procedure with undue casualness.) The Democrats have made a similar decision to talk about wanted babies and unintended consequences.

Another successful part of the Irish strategy was encouraging men to talk about the effect of abortion restrictions on them. (The campaign even included a group called “Grandfathers for Yes.”) That might raise feminist hackles, but the emotional impact of hearing someone like Josh Zurawski describe watching a loved one suffer unnecessarily—and his fears about losing his wife, as well as their baby—is undeniable. “I’m here because the fight for reproductive rights isn’t just a woman’s fight,” Zurawski told the convention, prompting cheers. “This is about fighting for our families.” Hearing him and Beshear—and the vice-presidential candidate Tim Walz on the campaign trail—talk about abortion shows the power of using an unexpected messenger. Notably, Beshear and others also spoke about girls and women, rather than the progressive, gender-neutral formulation of pregnant people—again demonstrating how this message is designed to appeal to voters beyond the Democratic base.

The Dobbs decision gave the right what it had demanded for half a century. But the ruling also made abortion an electoral liability for the Republicans. Even the most avowed pro-life campaigners struggle to articulate why women like Halappanavar and Zurawski should be left to die, and girls like Hadley Duvall should have their stepfather’s baby.

Abortion is on the ballot in November, and in a measure of how much the landscape has changed since the last election, it is also on the program here in Chicago.