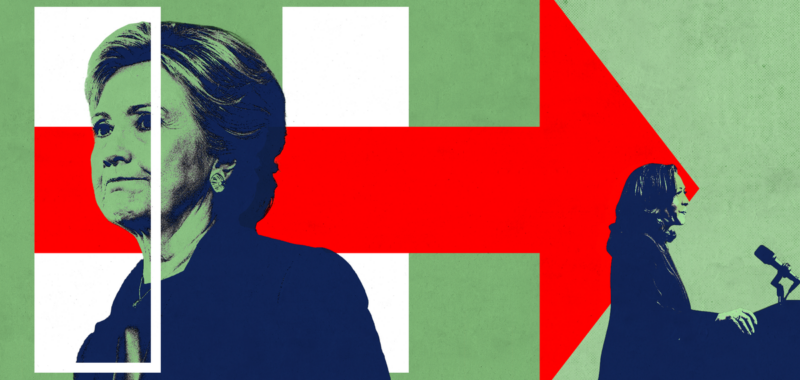

Amid all the Democratic excitement about Vice President Kamala Harris’s historic presidential candidacy, Hillary Clinton’s 2016 loss to Donald Trump lingers like the ghost at the feast.

Now Harris’s sudden ascension as her party’s presumptive nominee is providing Democratic women with a second chance to elect the first female president and break what Clinton often called the “highest, hardest glass ceiling.”

By any standard, Harris has benefited from an astounding outpouring of enthusiasm since President Joe Biden announced that he would no longer seek reelection. But her nascent campaign still faces some of the same challenges that Clinton’s did. The first polls measuring Harris’s support have generally not found women flocking toward her in unusually large numbers. And some grassroots Democrats otherwise euphoric about Harris remain concerned that too many voters, including plenty of women, will not accept a woman president.

How gender has evolved as a factor in presidential politics in the eight years since Trump’s unexpected victory will likely emerge as a pivotal feature of this reconfigured 2024 race. Perhaps even more than in 2016, Trump aims to embody a hyperbolic definition of masculinity, surrounding himself with pro wrestlers and emphasizing his physical courage after the assassination attempt a few weeks ago. Harris, for her part, is highlighting questions of gender equity even more explicitly than Clinton did, framing Republican efforts to ban abortion as part of an overall effort to reverse women’s gains in society.

These stark contrasts—reinforced by Harris’s status as the first woman of color atop a major-party national ticket—set the conditions for an election contest that could make America’s changing landscape of race and gender a central element. That prospect came sharply into view yesterday when Trump, speaking to an audience of Black journalists, suggested that Harris identified as Black solely for political advantage.

The positive trends for women in politics since Clinton’s defeat are unmistakable. The Reflective Democracy Campaign, a nonpartisan group that does research and political organizing related to race and gender, recently released an analysis showing that women have increased their share of elected offices at the state-legislative level or higher from one in four in 2014 to one in three today. Women of color have doubled their share of all elected offices from one in 20 then to one in 10 now.

“Absolutely people are more accustomed to women in elected office than they were 10 years ago,” Brenda Choresi Carter, the group’s director, told me. “Just numerically, there are a lot more women in elected office. More people are living with that reality, and more people are voting for that reality.”

The group also found that gains have come in all parts of government. Women have significantly increased their representation in both state and federal offices, and in both legislative and executive-branch positions. “This is a trend, really a phenomenon, across geographies, blue states and red states, levels of office, really nationwide,” Carter said.

Attitudes about women as leaders are improving too. In surveys conducted by Tresa Undem, a pollster for progressive causes, the share of adults who say that men make better leaders than women slipped from 16 percent in 2016 to 13 percent in 2022, while the share who say that women make better political leaders than men more than doubled over that period, from 6 percent to 14 percent. The majority of adults surveyed—77 percent in 2016, 73 percent in 2022—say that both genders are equally qualified to serve as leaders.

Although some Democrats worry that Black and Latino men may be more resistant to women leaders, Undem said her data show that a rising share of both groups agree that women make better political leaders. (The share of Black men expressing that view has more than quadrupled since 2016 from 5 percent to 22 percent, she found.) To the extent that Trump is gaining among men of color, “that growing openness,” Undem told me, “is unrelated to gender—it really is economic in nature,” centered on a belief that he can manage the economy more effectively than a Democratic president. This suggests that Harris, rather than facing intractable objections rooted in her identity, has an opportunity to regain at least some ground with men of color if she can mount a persuasive economic case.

Jennifer Lawless, a political scientist at the University of Virginia who has extensively studied the experience of women in politics, told me that other academic and media surveys have found a growing willingness to consider women appropriate leaders across a wide range of professional fields. She sees “very little difference in how male and female candidates and how male and female leaders in other industries” are viewed. “Over time, gender stereotyping has declined considerably,” she said. “Generally, there is not a predisposition any longer to think of a man as stronger than a woman in the same job.”

These trends notwithstanding, views about gender roles are a major partisan dividing line. Over the past generation, voters have become more sorted into the two parties according to their attitudes about demographic, cultural, and economic change in America—and that includes new patterns in gender relations. As I wrote in 2012, Republicans have established a dominant advantage among the people and places most uneasy with these fundamental changes, forming what I called the “coalition of restoration.” Correspondingly, Democrats have performed best with voters who are most comfortable as part of a “coalition of transformation.”

This re-sorting of the electorate reached a peak in the Clinton-Trump race. The best evidence from multiple academic studies of the 2016 election is that both men and women were more polarized in that contest than in 2012 over their attitudes toward demands for greater equity from women and racial minorities. In their 2018 book, Identity Crisis, the political scientists John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck found that white women and especially white men who expressed the most sexist attitudes voted for Trump at higher levels than voters with those same attitudes who had backed the 2012 Republican nominee, Mitt Romney.

In another landmark study of the 2016 result, the Tufts University political scientist Brian F. Schaffner and two co-authors showed that the best predictors of support for Trump were, in order, hostility toward demands for greater racial equity and hostility toward demands for greater gender equity; each attitude correlated with Trump support more powerfully than economic discontent did. Clinton came out ahead with voters who expressed the most concern about these inequities.

This stark separation of voters in 2016 set a new mold, emphasizing that attitudes toward social and economic change had become the clearest, most consistent distinction between the two parties’ coalitions. “The 2016 race changed the landscape of what was being contested in politics,” Vavreck, a professor at UCLA, told me.

The actual personalities on the ticket may not be all that significant. According to Schaffner, attitudes toward racial and social change predicted support for candidates as powerfully in the 2018 congressional elections as they had in 2016, even without Trump or Clinton on the ballot. In 2020, when the presidential race reverted to the historic pattern of two male candidates, Biden ran only slightly better than Clinton had among voters who expressed the most sexist attitudes, Schaffner found, while Trump ran slightly better than his own showing four years earlier among those who expressed the least sexism.

The 2020 race nevertheless followed the basic grooves of 2016, Schaffner told me, with voters still sorting markedly over gender roles and racial equity. Similarly, Undem found that not only men but also women voting for Trump were far more likely than Biden supporters of either gender to agree with such statements as “Society seems to punish men just for acting like men”; “White men are the most attacked group in the country right now”; and “Most women interpret innocent remarks or acts as being sexist.” Women as well as men who voted for Trump in 2020, she reported, expressed overwhelmingly negative views toward the #MeToo movement, which had emerged during his presidency.

All of this suggests, as Schaffner told me, that 2016 culminated in a “mini-realignment,” such that voters who “have a more traditional view on the role of women in society” shifted toward the GOP, while those with “a more feminist view” moved toward Democrats.

Given this history, whether the two parties’ coalitions will differ in their views about gender roles is beyond question. What remains to be seen is whether that divide will be wider because a female nominee is on the ballot again—and which party may benefit more from that.

Schaffner, like others I spoke with, believes that virtually all of the voters who would be uncomfortable with a woman or a person of color (or both) as president were already supporting Trump—and that this was true even when Trump was presumptively running against Biden, an 81-year-old white man.

“There are not a lot of sexist people who were going to vote for Joe Biden anyway,” said Schaffner, who is also a co-director of the Cooperative Election Study, which conducts a large-sample survey of voters during election years. “It’s hard to say that it doesn’t cost [Harris] maybe one point on the margin, because we can’t really measure things that precisely. But I can’t imagine it would be more than that, if it’s anything at all.”

Lawless similarly believes that Harris will not face as much resistance based on her gender as Clinton did. Gender politics were arguably more fraught for Clinton both because she was the first female major-party presidential nominee, Lawless told me, and because she had been a controversial figure since Bill Clinton’s presidency in the 1990s. “In terms of Clinton 2016,” she said, “it’s hard to know how much was sexism and how much was Hillary Clinton–ism.”

Many Democrats are cautiously optimistic that the ad hominem jabs against Harris rooted in her race or gender—such as the one from a Republican senator who called her a “ding-dong”—might backfire for Trump by reactivating younger women and nonwhite women who had seemed unenthused about voting for Biden. Celinda Lake, a Democratic pollster who studies gender dynamics in the electorate, told me that she believes Harris’s background as a district attorney in San Francisco and as the attorney general of California will help neutralize Republican claims that she’s not strong enough to protect Americans as president. “The strength axis was very, very damaging to Biden, but I think she answers a lot of the strength questions,” Lake said. “Then, for Trump, the questions of his kind of strength become more operational. Trump’s strength brings a lot of other qualities: divisiveness, ego … To some women, it brings toxic masculinity.”

Harris’s campaign also offers an opportunity for a reconciliation among liberal white women and women of color, many of whom had felt marginalized by Clinton’s campaign operation (although nonwhite women did overwhelmingly support Clinton, while a majority of white women backed Trump). Many activists believe that the cross-racial cooperation among women seems much more genuine for Harris than it was for Clinton. Largely spontaneous Zoom calls with huge attendance figures—to organize support first among Black women, then among white women, and then among white men—testify to an eruption of energy around her candidacy and a shifting dynamic among activist women.

“This is different,” Aimee Allison, who founded the group She the People to elect more women of color partly in response to the frustrations of the Clinton campaign, told me. “You had white women who said explicitly in that call ‘that we delivered the presidency as a group to Donald Trump in 2016 and that’s something we have to contend with—and now we look to Black women in particular for leadership.’ Their language of solidarity is evolving right before my eyes.”

Harris faces plenty of obstacles in her quest to shatter the glass ceiling. Besides discontent over inflation and other aspects of Biden’s record, she will need to demonstrate her own qualifications against Republicans disparaging her as a “DEI hire,” and rebut Republican efforts to portray her as an extreme liberal whose policies will lead to more crime and to chaos at the border. Those GOP efforts are aimed primarily at voters in the preponderantly white and older Rust Belt battlegrounds that are at the top of both parties’ target list: Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

But Allison, the She the People founder, believes that Harris’s candidacy could mobilize enough people of color and younger people to prove to the Democratic Party that it can win without concentrating so hard on courting culturally conservative older and working-class white voters. The old playbook, she told me, said, “‘Let’s bank on the more moderate voter as the center of our campaign; let’s have events and messaging that they will appreciate, and focus on older white voters.’ Now we have to be thinking differently.”

As a child of immigrants from Jamaica and India who is in a mixed-race marriage herself, Harris embodies the changes remaking America even more comprehensively than Clinton or Obama did. Although Trump has been attracting more support from Latino and Black voters than he did in earlier races, his campaign message remains centered on an implicit pledge to resist those changes and restore a social hierarchy in which white Christian men wield authority. With her braided identities, Harris could, by winning, show that “many more segments of society understand that there’s no one dominant group—that everyone is in the mix,” as Allison put it. The question of whether a rapidly diversifying nation will share power in new ways is on the ballot once again, perhaps even more pointedly than when Clinton ran. With Harris on the ticket, America has an opportunity to choose a different answer.