Photorealism has always been confusing. A genre of mostly paintings whose subject matter is photographs and whose prevailing style is precise illusionism began to emerge in the late 1960s. From the get-go, it was controversial.

The 20th century had seen pure abstraction claimed as visual art’s pinnacle. Paintings dependent on photography’s figurative images faced a steep climb.

The insecure bafflement over Photorealism was reflected in a sudden ‘70s glut of competing terms — Superrealism, Hyperrealism, Sharp-focus Realism, Post-Pop Illusionism, New Realism, Radical Realism. Add the contemporaneous arrival of a lively market for contemporary art, which had barely existed earlier in 20th century America, and all those rival brand names could seem like desperate promotional efforts to crack the market with comfortably retrograde, highly salable pictures.

At the Museum of Contemporary Art, “Ordinary People — Photorealism and the Work of Art Since 1968” is one attempt to refocus the subject. The show does a pretty good job of it, despite a couple of strange omissions and some odd inclusions. Generally, perspective is gained.

A few of its artists have always been embraced for conceptual rigor — most prominently Vija Celmins, whose images copy photographs of deserts and seascapes, as well as book and magazine pictures; and the late Chuck Close, whose giant paintings enlarge photographs of portrait heads. Many others — painters of Pontiacs, drugstore facades or gumball machines — were dismissed as frivolous.

But it was never exactly clear how or why. Choosing to make a detailed painting of a photograph itself created an abstraction — if “abstract” is defined as the quality of dealing with an idea, rather than an event. Somehow, that simple notion was hard to grasp. Maybe photography’s then long-standing status as a lesser art was part of the reason why.

“Ordinary People — Photorealism and the Work of Art Since 1968” highlights two aspects, both keyed to its somewhat cumbersome title. First, the field is enlarged to include top-notch artists in subsequent generations, whose work reflects an ongoing Photorealist legacy. And second, an often ignored quality of the work is given a serious look.

That largely disregarded element is the simple fact that Photorealist art is labor intensive. MOCA curator Anna Katz and curatorial assistant Paula Kroll emphasize the work in a work of art.

Work applies to the production of any significant art, of course, even when the material is an object found in a dumpster, or a set of instructions typed on a sheet of paper. We’re not talking about coal mining or Amazon home delivery here, but Photorealism does look laborious. It wears work on its sleeve.

Celmins’ 1968 drawings of old black-and-white photographs torn from history books — a 1930s zeppelin airship, Hiroshima’s nearly obliterated 1945 landscape — begin with a sheet of paper prepared with a ground of snow-white acrylic. The surface is made receptive to the delicate movements of soft graphite across the page. Careful pencil marks are placed on an aesthetic pedestal, while the speed of a camera’s shutter-click in shooting the source material is slowed to the crawl of a careful drawing.

The result is a palpably concentrated, disarming sense of focus. Your eye responds to the artist’s subtle touch. Suddenly, it occurs that the chosen scenes favor things that cannot themselves be touched — aerial flight high overhead, out of reach, or deadly radioactive space left by an exploded nuclear bomb. Historical memory is likewise remote. Thought fills these voids, and an unexpected moral grandeur blankets images lavished with such care. Subject matter and art object fuse.

Half a century later comes Cynthia Daignault’s provocative “Twenty-Six Seconds,” a MOCA commission for the show from the Baltimore artist, newly completed and having its debut. Its subject is the famous 1963 Abraham Zapruder film, which recorded the Dallas murder of President Kennedy. Daignault painted each of the film’s 486 frames on separate 8-by-10-inch canvases — the size of a standard still photo — and installed them in a grid, 18 canvases high and 27 wide. It’s monumental, like the event.

The paint handling is loose. Each form or shadow is constructed from a brushstroke, introducing the artist’s hand into the cold machinery of camera work. The moments before the fatal shooting fill the grid’s upper half, while the tragic denouement unfolds at a viewer’s vulnerable eye-level. The horrific, lethal, split-second impact comes in frame 313, seven rows up from the bottom and 16 frames to the right, where a burst of vertical light interrupts the horizontal flow of the terrible pictorial narrative.

After another row or two, Daignault’s canvases become increasingly abstract, finally dissolving into blurred daubs of color against black fields. As a meticulous representation of the inexplicable, which clings to arguably the most censored and conspiracy-riddled major episode of modern American history, “Twenty-Six Seconds” is both remarkable and moving.

Needless to say, Daignault’s “Twenty-Six Seconds” took far longer to make than Zapruder’s. Katz, writing in the show’s catalog, reasonably speculates that the visible labor involved in Photorealist art is one reason first-generation examples weren’t well received. Art is a conversation among artists, making the contentious history of avant-garde art a highly specialized field. But suddenly, a general public could embrace the Photorealist genre — partly because the images were recognizable, yes, but equally because the detailed precision represented hard work.

“My child could do that” is the cliched (and erroneous) refrain of the uninformed viewer of Modern art, especially abstraction. Now, the response flipped. The art world was dismissing the popular reception of Photorealism with a similarly narrow-minded explanation: Ordinary people, whose experience was being represented, liked it. Katz suggests that the artists’ apparent desire for a popular hug alienated a cloistered art public.

To top it off, the curators underscore something few are willing to acknowledge: As a technical matter, almost anyone can learn to draw and paint realistically. With enough practice, your child could probably get the hang of it too. As technique, Photorealist competence is just a matter of — well, work.

To demonstrate, Close’s meticulously detailed head of mustachioed “Robert,” 9 feet tall, is installed next to its maquette, an enlarged and subdivided black-and-white photograph overlaid with a tight grid. Close just had to replicate the tiny squares of darks and lights on his canvas, like following a map. It was a whole lot of work.

Almost half of the 44 artists in “Ordinary People” are first-generation, born in the tumultuous period between the Roaring ’20s’ collapse into the Great Depression and the end of World War II. They matured during decades when camera images, still and moving, from broadsheets and tabloids to television and CinemaScope, became ubiquitous in American life. In retrospect, the fact that camera images themselves would become a subject seems inevitable.

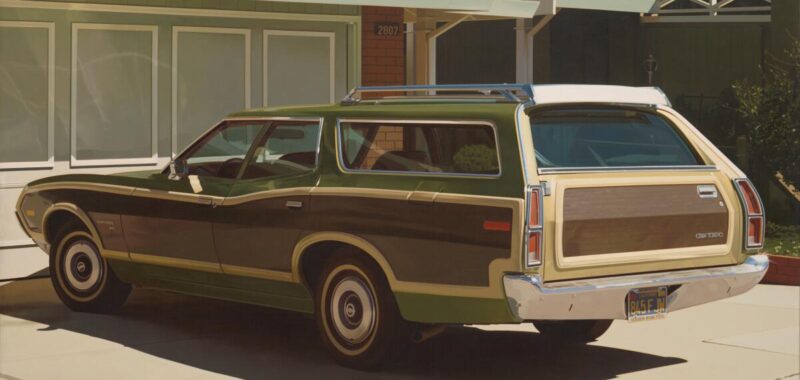

Like the rest of the art scene, the genre’s earliest noted practitioners were almost exclusively white males. Among them are Robert Bechtle, portraitist of automobiles, including a shrewdly chosen Gran Torino station wagon whose wood paneling modernizes the Conestogas of manifest destiny; Richard Estes and Ralph Goings, recorders of urban and suburban shops and diners; and Richard McLean, whose leisure-rodeo cowboys and cowgirls are cosplay hobbyists.

Katz expanded the horizon, especially for subsequent generations.

Among the superlative examples since the ‘80s are wall-size works by the team of John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres, whose sculptural reliefs of kids at play transform the mural tradition. Judie Bamber’s small drawings and watercolors of her father’s intimate photographs of her mother bring hidden familial dynamics into anxious view. Takako Yamaguchi’s exploded close-ups of women’s clothing — trench coat, striped skirt and belt, crochet top — morph into strangely geometric abstractions.

Exquisite pastel portraits of Latino friends and neighbors by John Valadez; an altar-like assembly of 46 panels by Ben Sakoguchi tracking the cold-eyed evolution of nuclear terrorism; a Kehinde Wiley promotional portrait of hip-hop aristocracy — the range is wide. Feminist sexual politics unfold in takes on commercial erotica by Marilyn Minter, Joan Semmel and Betty Tompkins; a wry and confrontational boudoir still life by Audrey Flack, like an overhauled ad from Glamour magazine; and Andrea Bowers’ surveillance-style paean to socially engaged working women.

Sometimes, though, the enlarged view slips out of focus. Marilyn Levine was an exceptional ceramicist who built detailed useful objects — shoes, garments and accessories (backpacks, handbags) — from useless slabs of fired clay. But her beguiling illusion of soft leather rendered as hard sculpture doesn’t betray any photographic subject matter.

Nonfunctional hyperrealism, yes; Photorealism, no.

Omissions are puzzling too. An obvious list would include Robert Cottingham’s signature landscapes of elaborate neon signage and Malcolm Morley’s souvenir postcards of cruise ships and recruiting posters of naval destroyers. Perhaps most unexpected is the absence of Charles Bell’s monumental toys and candy machines, which explode harsh photographic light, as well as Richard Artschwager’s acute architectural constructions painted on Celotex board, a building material that serves as an ironic ground for precision pictures of offices being demolished or off-kilter tract homes.

MOCA, in its permanent collection, has terrific — and pertinent — photo-based examples by Morley and Artschwager. But they’re not included, perhaps to make room for new works like Alfonso Gonzalez Jr.’s big “Pawn Shop,” a wall-size compendium of commercial advertisements mixing poignancy with desperation, and Sayre Gomez’s haunted street-side shrine to an anonymous urban death.

Glowing below background signs for a liquor store, a laundromat and an Echo Park burger joint, Gomez shrewdly identifies the specific street through a blazing sunset, glimpsed off in the distance. Pacific life is far away. The coming veil of darkness is announced with a jab of 2024 topicality. “Ordinary People” neatly puts to rest any lingering skittishness about Photorealist validity.